Understanding and Encouraging the Development of Hockey IQ

A few years ago, I was out for a skate and found myself watching a Junior kid and thinking, “man, this guy is so dumb out there.” The words slipped out before I even realized what I was saying.

Then it hit me—I coach in the same area this kid grew up in. Whether I had him directly or not, I’m part of the system that shaped him. So if his hockey IQ is low, it’s not just his failure. It’s partly mine. Partly ours. That realization kicked off a rabbit hole that I’m still working through.

What is hockey IQ?

I started asking around. Friends of mine who got paid to play or coach the game gave me their take on the concept. The answers were insightful—each one touching on a different piece of the puzzle. But they didn’t quite snap together into something you could hand to a player or a parent and say, this is it. It was like trying to unify quantum mechanics with general relativity—lots of truths, no single theory.

None of the replies seemingly unified the concepts:

Mike Komisarek (11 seasons in the NHL, Defense, Wolverines, Player Development Coach-Vancouver Canucks, hockey dad) put it like this:

“Elite hockey IQ isn’t flashy plays, it’s obsessive execution of the simple, repeatable, unglamorous decisions that never hit the highlight reel. It’s cataloging the wins, owning the mistakes (chewing on them just long enough to learn, then letting them go), and immediately caring more about the next right play than the last screw-up or the scoresheet. It’s supporting the teammate who just got burned, because NHLers make tons of mistakes every night—and the best ones turn them into fuel, not anchors. Process pride. Relentless detail. Total commitment on every shift. That’s the common thread. That’s the standard.”

Max Pacioretty (17 seasons in the NHL, LW, Wolverines, coach/hockey dad) identified differences in payout/non-payout scenarios:

“Kids are obsessed with scoring goals and their hockey IQ seems just fine when they are in a position to score goals. But their inability to care about the 99.9% of other plays that don’t directly result in a scoring chance is alarming. So is it an IQ dilemma in other areas of the ice? Or, is there just no more pride in stacking good plays and worrying about the process rather than the results (goals)?”

Blake Wheeler (16 seasons in the NHL, RW, Golden Gophers, coach/hockey dad) said:

“Competing to win battles, supporting teammates-knowing where and how to support the puck, and the details of doing your job (accountability).”

Steve Shirreffs (3 seasons in the AHL, Princeton All-American, Defense, Principal Granite State Capital, coach/hockey dad)

“The most basic principles of the game are protecting the front of your net, don’t turn the puck over at the blue lines, forecheck/backcheck, move the puck up the ice to teammates, follow the play/gap control, get shots on net. When I think of someone with a high hockey IQ, I think of someone who is able to think the game to create offensive chances for himself or teammates.”

Daryl Jones (Yale Bulldog, former part-owner of the Phoenix Coyotes, Owner/Director of Research-Hedgeye, the Gold Coast’s Most Eligible Bachelor, The Real Most Interesting Man in the World, coach/hockey dad):

“When I think about hockey IQ skills, I believe they’re scanning, anticipation, risk/reward assessment, positioning with and without the puck, and awareness of the other team’s systems.”

Matt Deschamps (AHL/ECHL, Black Bears, U. Michigan Assistant Coach, hockey dad):

“I think the basics of hockey IQ are simple, it’s seeing time and space.”

How was I to make sense of these seemingly disparate views? The defensemen had a nuanced view from the forwards. The coach had a very simple interpretation. Was there any agreement?

Then I got a reply from Matt Moulson (11 seasons in the NHL, Big Red, LW, coach/hockey dad) that hit like a bag of pucks dropped from the rafters to the head—but in the best way.

“Hockey IQ starts with knowing yourself—really knowing what you’re capable of. Most so-called ‘dumb’ plays are just players overestimating their skillset and trying low-probability plays. Once you’re honest about what you can do, the game becomes a fluid puzzle. No two situations are the same, but patterns repeat. So you start solving problems in real time—based on your tools, your teammates’, your opponents’, and the context of the game. Every decision is a split-second calculation of risk vs. reward.”

That was it. That was the bridge.

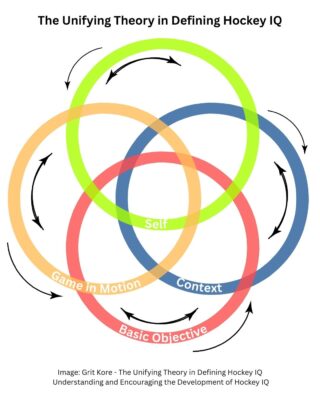

The game isn’t just about smarts with the puck. It’s about being in tune—with yourself, your team, your opponent, and the game itself. That’s when I started thinking of hockey IQ in terms of layers. Overlapping rings, each one spinning at the same time.

Let me break it down.

One ring is the basic objective of the game: score more goals than the other team. Simple. Possess the puck longer. Regain it quicker. Capitalize more often. That’s the scoreboard layer.

The next ring is the game in motion—reading plays, understanding team dynamics, adapting to flow, sensing momentum shifts, knowing your assignment and anticipating where things are going next.

Then there’s context: the score, the clock, your shift length, opponent tendencies, energy level, where you are in the season, what’s happened earlier in the game. That’s real-time game management.

And unifying the three rings is the self. Honest self-awareness. Knowing what you’re great at and what you’re not. Making decisions that serve the team, not your ego. Owning your role, even if it’s not the one you want. Trusting the system. Holding yourself accountable even when the mistake wasn’t fully yours. That’s the heartbeat of hockey IQ.

Visually, we can picture hockey IQ as follows:

And here’s the kicker—these aren’t stages you walk through. These layers are simultaneous. They spin together. The highest IQ players? They don’t think about each layer in order. They line them up instantly, like dials clicking into place. And when they do? The game slows down. It clicks. It flows.

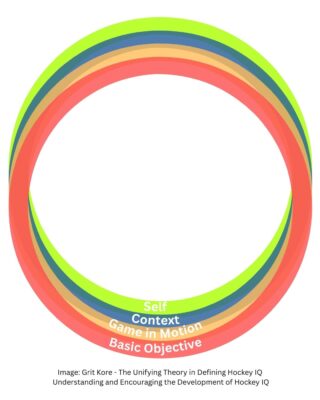

It’s not just cognition anymore—it’s rhythm. A lot of players commented on ‘being in the present’. There was no prefrontal cortex activation, it was feeling all of the circles at once:

This isn’t something you just drill into a kid with reps, privates and whiteboards. This is about training awareness. Pattern recognition. Self-honesty. Accountability.

In the area I am in, players are doing countless hours of skill work. And, I am starting to wonder if the over-emphasis on skill development at a young age is encumbering hockey IQ development. For example, players may not need to think at the U8 and U10 level because they have a short-term skill advantage over other players (one that erodes as they matriculate through U12, U14 etc).

Hockey IQ vs. Cognitive IQ — What Coaches Need to Understand

One of the most revealing insights that came from these conversations was this: hockey IQ isn’t distributed equally, just like cognitive IQ. Some players naturally process information faster, read plays more intuitively, and make better decisions under pressure.

But just like with academic intelligence, hockey IQ isn’t fixed.

A kid who holds onto the puck too long may not be selfish — they might simply be struggling to read the game in real time. That doesn’t mean they can’t contribute. If they’re passionate, coachable, and held accountable, they can develop awareness, improve pattern recognition, and become a smarter, more impactful player. We hope our daily/weekly problem solving scenarios will help those players.

The takeaway? Coaches need to understand that not every player sees the ice the same way — and that’s okay. Our job isn’t just to drill skills, but to teach thinking. To build hockey intelligence just like you’d develop any other form of problem-solving.

Patience. Guidance. Accountability.

With those in place, even a player who’s not the fastest thinker can still become one of the smartest players on the ice.

A heartfelt thank you to all the hockey minds who generously shared their time, stories, and insights to help shape this framework. I might be the one putting words to it, but the real structure — the bones of this model — comes from those who’ve lived it at the highest levels.

Find. A. Way.

— Greg