While watching an NHL game with my son the other night, I caught myself trying to explain something most fans never even notice: how acceleration works on the ice, and why great players are constantly managing the natural delay it creates in the rhythm of the game. One simple question led to another, and, if you’ve been following our blog, you know exactly what happens next. I had to dig deeper.

Pretty soon I was knee-deep in physics, breaking down the difference between on-ice and off-ice acceleration so we could visualize it clearly and help young athletes understand why it matters for their game.

And here’s the big takeaway:

Acceleration on skates is not the same thing as acceleration in sneakers.

Not even close.

Understanding that difference can completely change how a kid reads the game, positions themselves, and makes decisions under pressure.

Let’s dig in.

1. The Physics Are Completely Different

Off the ice — running on turf — you have something incredibly valuable on your side:

Grip. High friction. Instant response.

You plant your foot, push hard, and the ground gives you exactly what you put into it.

On the ice?

Low friction and glide.

The skate blade slides before it bites, forcing you to use edge angles, hip rotation, and controlled pressure to generate force.

This is why a kid who looks explosive in sneakers might not look explosive on the ice — and why another kid who looks average during dryland suddenly becomes electric when the blades hit the sheet.

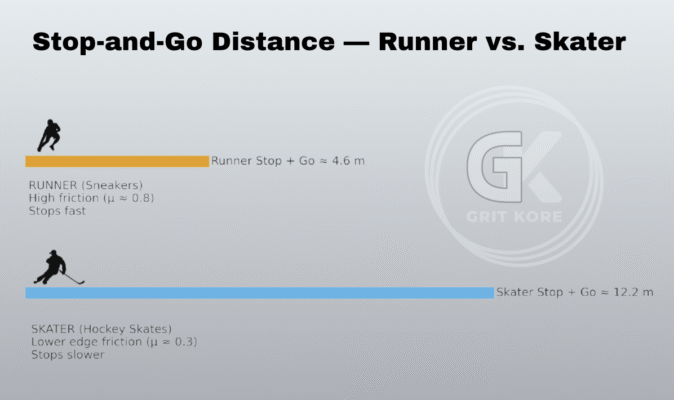

2. A Simple Comparison: Runner on Turf vs. Skater on Ice

To really make this clear, let’s compare the same movement:

A full-speed stop → turn → re-acceleration back to full speed

We’ll assume both the runner and skater approach at the same speed (6 m/s, about 13.4 mph).

Runner on Turf

- High friction (µ ≈ 0.8)

- Can stop fast and push off again almost instantly

- Total stop+go time: ≈ 1.5 seconds

- Distance needed to complete stop+go: ≈ 4.6 meters

Skater on Ice

- Even in a strong hockey stop, friction is much lower (µ ≈ 0.3)

- Takes longer to create enough bite to decelerate

- Total stop+go time: ≈ 4.1 seconds

- Distance needed: ≈ 12.2 meters

In other words:

A skater needs about 3× more time and 3× more space to perform the same stop-and-go as a runner.

That difference affects every read, angle, and decision in hockey.

Here’s the visual we created to make this clear:

In the coming weeks we’ll explore how the most effective zone entry tool in U8 hockey — the toe drag — becomes a handicap at older ages unless players understand transition times. Without adapting to changes in momentum, timing, and space, what once worked effortlessly can actually disrupt team flow and create vulnerabilities.

Find. A. Way.

Greg